How to Talk About Death & Grief with Young Children

Talking to young children about death and grief is a deeply sensitive and profound task. Many adults feel uneasy just mentioning the word "death"—do you also feel a wave of anxiety or fear when discussing it? Or are you able to stay relatively calm? Everyone holds a natural reverence for death to some degree, but before engaging in such a conversation with a child, it's important to first acknowledge and accept your own emotional state. If we are overwhelmed by sadness or anxiety, that emotional turbulence can silently pass on to the child, deepening their confusion and fear.

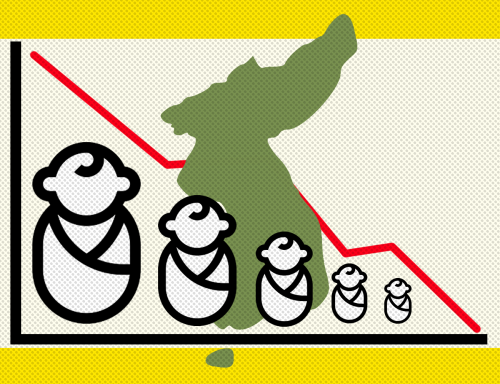

Although death is a life event we will all face eventually, losing a loved one earlier than expected often brings immense grief. Children need support that is specially tailored to their developmental stage in order to help them process and navigate the experience of loss. They may not fully grasp the concept of "forever," but they can still sharply sense changes in their environment, emotional shifts in adults, and the somber tone in the air. Avoiding the topic isn’t helpful—instead, we should be brave enough to face it with them.

In reality, children are exposed to the concept of death early in life: wilting flowers, a dead bug, characters dying in storybooks, or even news reports. If parents deliberately avoid talking about death—neither explaining nor responding—it leaves children to fill in the gaps with their own imaginations, which might be more frightening or unrealistic, increasing their anxiety.

We must understand that death is inherently mysterious and awe-inspiring. What happens after we die? It's a question humanity has asked for centuries without a clear answer. While medicine can explain the physical aspects—heart stopping, breathing ceasing, brain activity ending—science has no definitive explanation for what happens to the "soul" or if there’s anything beyond. This uncertainty fuels fear and imagination. Most adults struggle to fully come to terms with it—how much more confusing it must be for a child.

Because of this uncertainty, many adults instinctively think, “The child is too young—better not tell them.” But this may increase the child’s unease. Even young children can sense emotional shifts or tension at home. If they’re not given an honest explanation, they may feel isolated, or even wrongly blame themselves, making the emotional burden heavier. So when a loved one dies, it’s healthier to tell them early, using age-appropriate language.

When you're ready to talk about death, pay attention to how the child reacts. Sometimes, they might suddenly burst into tears—not just out of sadness for the one who died, but from a deeper fear of separation: "If Grandma is gone, will Mommy and Daddy leave me too?" This fear might not be spoken aloud, but parents need to hear the unspoken question behind the tears and respond gently to it: “Mommy and Daddy will always be here for you.”

The way we talk about death should be tailored to the child’s age and level of understanding. For very young children, you might use familiar metaphors: “Just like a flower wilts at the end of its life, people also leave this world when their time is up.” For older children, you can be more direct: “Death means the body stops working, and the person’s spirit leaves their body—we won’t see them again.”

When a child asks, “Where do people go when they die?” don’t rush to give a fixed answer. Try asking, “What do you think?” Then gently offer an open response: “Some people believe they go to heaven. Others think it's like a long, peaceful sleep. We can’t be sure, but the love they gave us and the memories we have will always stay in our hearts.”

Children often express emotions in non-verbal ways—through drawing, pretend play, or storytelling. Adults can support them by encouraging these forms of expression. For example, if a pet dies, you could bury it together, draw pictures in its memory, and share warm stories about it. These rituals aren’t just farewells; they’re part of the healing process.

As we help children understand death, we should also guide them to see the beauty of life. Death reminds us that life is finite, and that’s exactly why each moment is so precious. Help them appreciate the joys in everyday life, and let them know: “Even though life ends, we can choose to love deeply, explore the world, and chase our dreams during the time we do have.”

Finally, remember that every child processes death differently. Some may move on quickly; others may stay in grief or confusion for a long time. Respect their pace. Don’t pressure them to “get over it,” and avoid saying things like, “You need to be strong.” What children really need is a caring adult who will listen, accept their emotions, and offer support. Being present with them in their most vulnerable moments is the most powerful comfort we can give.

Teaching children about death isn’t about making them sad—it’s about helping them understand, accept, and respect life itself. We can’t prevent loss, but we can guide them to love through grief, remember with tenderness, and continue walking forward—with love.

Recommended for you: